All_In

Gold Supporter

- Joined

- Apr 21, 2008

- Messages

- 16,105

- Location

- San Diego, CA. USA

- Aircraft

- Airgyro AG915 Centurian, Aviomania G1sb

- Total Flight Time

- Gyroplane 70Hrs, not sure over 10,000+ logged FW, 260+ ultralights, sailplane, hang-gliders

Warning all newbie’s do not think this is correct information in anyway many of my friends here think it will change with experience! It is just to teach myself and it’s a test to see how much of it changes after I have several 100 hours.

----Start----

Flying behind the power cure

So how does an aircraft fly "behind the power curve" and what happens when you do?

First lets’ answer how do you avoid it. It is simple just keep your airspeed above minimum straight and level flying speed by watching your airspeed indicator.

Flying behind the power curve means the point (airspeed) at which more power is required to maintain the same altitude and you start an uncommanded descent . The lower the airspeed the further behind the power curve you are and the faster you uncommanded decent becomes until you hit zero airspeed and you start a vertical uncommanded decent.

Now what happens and why many accidents occur in gyroplanes from not having enough power in to maintain the airspeed to maintain altitude. This is usually because the angle of attack and your pitch is too high with the power setting you have even full power when taking off and climbing out at too steep an angle which reduces your airspeed and you then will descend until you hit the ground. That is how most of these accidents occur on takeoff when the pilot does not take action by reducing pressure on the cyclic which lowers the nose and adding power, if any power left. It can also occur when turning base or final at minimum air speeds.

With full power the pilot’s only action to avoid it is to increase airspeed by reducing back pressure on the cyclic to gain airspeed. Bensen described how to get out of it as diving down. With full power in accidents I believe this scares pilots diving towards the ground and they freeze instead of reducing their pitch and fly down and level out only inches above the ground then fly parallel to the runway gaining airspeed. This last maneuver is use for short field takeoff procedures with runway without obstruction at the end.

Gyroplanes can safely fly behind the power curve it when you get trapped there that it become an accident.

It also can occur when landing and the pilot has reduced power having only enough airspeed to fly straight and level however when they bank on base or final with this low airspeed you will start to descend until you hit the ground unless you level out again which will increase airspeed back to where it was but you should add power increasing it to a safe airspeed, more on banked turns later.

Gyroplanes will not stall they will go into a decent because our airfoils will only stall when they approach supersonic airspeeds starting at the blade tips and only happens at very fast air speeds not slow air speeds However they will enter an uncommanded decent until they hit the ground.

How to experience this yourself and I suspect that your pilot operating handbook doesn't have a set of power curves so here how to have both.

The next time you fly with an instructor, if not an experienced pilot, take the time to collect data for drawing your own power curves. It's really very simple. Do this at a safe altitude with plenty of time to recover.

1. Trim the aircraft for straight and level flight at a cruise power setting. Write down both the AIRSPEED and power setting.

2. Then reduce your airspeed in 10-kt increments without changing from straight and level and continue to record airspeed and power settings.

3. Eventually, you will reach a point at which more power is required to maintain the same altitude with a NOTICEABLE slower airspeed.

4. You are now officially "behind the power curve."

5. Once you know you're on the back side, push the nose over and observe what happens. Your AIRSPEED will increase and even with the same low power setting you are no longer behind the power cure.

6. Then raise the nose and make some similar observations. Your airspeed will decree and a gyroplane will start descending. The higher the angle of attack the faster the gyroplane descends.

7. Continue to do this while maintaining altitude. When you have finished, you will know exactly how your Aircraft will act while flying under these circumstances.

8. You should also explore directional control at low indicated airspeed and practice turns as if turn base or final at different bank angles.

9. Once you have mastered how to physically fly your Aircraft behind the power curve, you can better keep from entering this flight regime unintentionally and will learn how to fly out of it.

TO AVOID IT JUST WATCH YOUR AIRSPEED INDICATOR and increase airspeed with power until full on and then lower your angle of attack and this will not happen! CANNOT happen with the correct airspeed no matter what the wind direction!

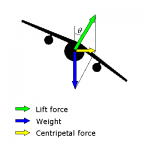

Now that you understand what flying behind the power cure mean let’s examine what happens during a banked turn where the lift on the aircraft must support the weight of the aircraft, as well as provide the necessary NEW component of horizontal force to cause centripetal acceleration. Because of centripetal acceleration the lift required in a banked turn is greater than one required in straight, level flight. All air foiled 'CLT' (center line trust) aircraft you must pull back on the stick in a banked turn. Why because any moving vehicle making a turn, it is necessary for the forces acting on the vehicle to add up to a NEW net inward force if you look at the picture there is a new horizontal force (centripetal acceleration) that is stealing some of your lift in a banked turn, examine the picture and see the yellow arrow. The more you bank the more it steals and the more power needed to hold the bank.

Gyroplanes to not stall at low airspeeds only descend too quickly and hit the ground hard often tipping over where most of the damage occur. Same in a car this force is what makes you slide off the road in a turn. Now pulling back on the stick even a little is going to increase your angle of attack increasing DRAG so a turn at LOW AIR SPEEDS will always require more power in any turn!

In all airfoil aircraft that are statically stable with respect to G-load it's necessary to use aft stick pressure to execute a level, banked turn at constant airspeed. In some HTL, statically unstable gyros, though, the fore-aft stick pressure feedback with changing G-loads is apt to be reversed. In these craft, it's necessary to add FORWARD pressure to avoid mushing out of a turn, once you've settled into your bank. Newbie’s flying uncompensated HTL in a gyro used to mush out of turns all the time and I’m told that when transitioning to a Dominator it was quite a revelation when they flew them for the first time and found it required AFT stick in a turn. The need for forward stick to hold speed in a turn is one quick way to diagnose uncompensated HTL in a gyro. It's not foolproof; much depends on the trim spring rate, head offset, spring setup and of other variables.

=================================================== No Audit Needed it is just a copy of of Dr Bensen's ===============================

To further explain curve graphs here is how Dr Bensen described them.

14. APPENDIX I

TO GYROCOPTER FLYING INSTRUCTIONS

The more technically-minded builders and pilots of Gyrocopters will appreciate the significance of this Appendix and its attached curves.

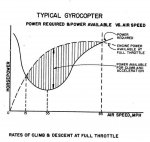

Two curves have been plotted on the following page, which describe better than words the relationship between flight speed and the engine horsepower of a typical Gyrocopter.

The first plot shows two curves, the solid one being power required to maintain steadystate level flight at a fixed gross weight, and the dashed curve shows engine horsepower available at any given forward airspeed. Several points are worth studying here. Observe first that even when turning at full throttle, engine power is zero at zero airspeed insofar as forward propulsion is concerned. This horsepower rises rapidly to the point where at 15 mph it can maintain level

flight. Beyond this point the pilot must reduce the throttle to maintain level flight. If he chooses not to do so, the craft will either rapidly accelerate to higher airspeeds, or will climb, or both, depending on what he does with his longitudinal stick control. Maximum excess horsepower occurs at 40-45 mph. Finally, at approximate!y 85 mph the “power required” curve crosses again the “power available” curve, which means that the gyrocopter here reaches its “top speed” in

level flight. Higher speeds beyond this point therefore can be obtained only at the expense of losing altitude, or diving.

The second plot illustrates this situation further by comparing it with an airplane of approximately equivalent horsepower and performance. It can be seen that the Gyrocopter performs best in the very area where an airplane quits flying because of stall, at about 40 mph. Furthermore, the Gyrocopter never really “quits flying” even below its “minimum level” speed of 15 mph, but continues to fly at a finite rate of descent. Even at zero forward speed this rate of descent is

comparable to that of a parachute.

One lesson a new Gyro pilot must learn after studying these curves is this: whenever he finds himself slowing down accidentally or on purpose to 15 mph (or if banked in a turn, to 20-25 mph), the only way he can check his descent, or initiate a climb, is to dive momentarily to 40-45 mph while opening the throttle wide open. If in a turn, also flatten out the bank as soon as possible. This may seem like an odd thing to do, especially if you are already close to the ground, nevertheless, if you want Mother Nature to cooperate, that is the proper thing to do. Your effort in will power will be richly rewarded by the gyrocopter possessing at 45 mph the rate of climb of

“a homesick angel”, pulling you out of tightest spots as it heads for the sky.

Also obvious from these curves is the “negative drag slope” below 45 mph, which means that, at a given power setting, the machine will constantly try to either speed up or slow down. To maintain constant airspeed below 45 mph then the pilot must constantly manipulate the throttle up and down to imitate governor action.

Other clarifications of the relationship between the horsepower and the airspeed will become apparent to you at length, if you take time to memorize and study the attached curves. Please note that the curves were drawn purposely not to scale to allow for the variation of performance between individual gyrocopters.

Here is an example of an accident: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AheudQuxZZY

----Start----

Flying behind the power cure

So how does an aircraft fly "behind the power curve" and what happens when you do?

First lets’ answer how do you avoid it. It is simple just keep your airspeed above minimum straight and level flying speed by watching your airspeed indicator.

Flying behind the power curve means the point (airspeed) at which more power is required to maintain the same altitude and you start an uncommanded descent . The lower the airspeed the further behind the power curve you are and the faster you uncommanded decent becomes until you hit zero airspeed and you start a vertical uncommanded decent.

Now what happens and why many accidents occur in gyroplanes from not having enough power in to maintain the airspeed to maintain altitude. This is usually because the angle of attack and your pitch is too high with the power setting you have even full power when taking off and climbing out at too steep an angle which reduces your airspeed and you then will descend until you hit the ground. That is how most of these accidents occur on takeoff when the pilot does not take action by reducing pressure on the cyclic which lowers the nose and adding power, if any power left. It can also occur when turning base or final at minimum air speeds.

With full power the pilot’s only action to avoid it is to increase airspeed by reducing back pressure on the cyclic to gain airspeed. Bensen described how to get out of it as diving down. With full power in accidents I believe this scares pilots diving towards the ground and they freeze instead of reducing their pitch and fly down and level out only inches above the ground then fly parallel to the runway gaining airspeed. This last maneuver is use for short field takeoff procedures with runway without obstruction at the end.

Gyroplanes can safely fly behind the power curve it when you get trapped there that it become an accident.

It also can occur when landing and the pilot has reduced power having only enough airspeed to fly straight and level however when they bank on base or final with this low airspeed you will start to descend until you hit the ground unless you level out again which will increase airspeed back to where it was but you should add power increasing it to a safe airspeed, more on banked turns later.

Gyroplanes will not stall they will go into a decent because our airfoils will only stall when they approach supersonic airspeeds starting at the blade tips and only happens at very fast air speeds not slow air speeds However they will enter an uncommanded decent until they hit the ground.

How to experience this yourself and I suspect that your pilot operating handbook doesn't have a set of power curves so here how to have both.

The next time you fly with an instructor, if not an experienced pilot, take the time to collect data for drawing your own power curves. It's really very simple. Do this at a safe altitude with plenty of time to recover.

1. Trim the aircraft for straight and level flight at a cruise power setting. Write down both the AIRSPEED and power setting.

2. Then reduce your airspeed in 10-kt increments without changing from straight and level and continue to record airspeed and power settings.

3. Eventually, you will reach a point at which more power is required to maintain the same altitude with a NOTICEABLE slower airspeed.

4. You are now officially "behind the power curve."

5. Once you know you're on the back side, push the nose over and observe what happens. Your AIRSPEED will increase and even with the same low power setting you are no longer behind the power cure.

6. Then raise the nose and make some similar observations. Your airspeed will decree and a gyroplane will start descending. The higher the angle of attack the faster the gyroplane descends.

7. Continue to do this while maintaining altitude. When you have finished, you will know exactly how your Aircraft will act while flying under these circumstances.

8. You should also explore directional control at low indicated airspeed and practice turns as if turn base or final at different bank angles.

9. Once you have mastered how to physically fly your Aircraft behind the power curve, you can better keep from entering this flight regime unintentionally and will learn how to fly out of it.

TO AVOID IT JUST WATCH YOUR AIRSPEED INDICATOR and increase airspeed with power until full on and then lower your angle of attack and this will not happen! CANNOT happen with the correct airspeed no matter what the wind direction!

Now that you understand what flying behind the power cure mean let’s examine what happens during a banked turn where the lift on the aircraft must support the weight of the aircraft, as well as provide the necessary NEW component of horizontal force to cause centripetal acceleration. Because of centripetal acceleration the lift required in a banked turn is greater than one required in straight, level flight. All air foiled 'CLT' (center line trust) aircraft you must pull back on the stick in a banked turn. Why because any moving vehicle making a turn, it is necessary for the forces acting on the vehicle to add up to a NEW net inward force if you look at the picture there is a new horizontal force (centripetal acceleration) that is stealing some of your lift in a banked turn, examine the picture and see the yellow arrow. The more you bank the more it steals and the more power needed to hold the bank.

Gyroplanes to not stall at low airspeeds only descend too quickly and hit the ground hard often tipping over where most of the damage occur. Same in a car this force is what makes you slide off the road in a turn. Now pulling back on the stick even a little is going to increase your angle of attack increasing DRAG so a turn at LOW AIR SPEEDS will always require more power in any turn!

In all airfoil aircraft that are statically stable with respect to G-load it's necessary to use aft stick pressure to execute a level, banked turn at constant airspeed. In some HTL, statically unstable gyros, though, the fore-aft stick pressure feedback with changing G-loads is apt to be reversed. In these craft, it's necessary to add FORWARD pressure to avoid mushing out of a turn, once you've settled into your bank. Newbie’s flying uncompensated HTL in a gyro used to mush out of turns all the time and I’m told that when transitioning to a Dominator it was quite a revelation when they flew them for the first time and found it required AFT stick in a turn. The need for forward stick to hold speed in a turn is one quick way to diagnose uncompensated HTL in a gyro. It's not foolproof; much depends on the trim spring rate, head offset, spring setup and of other variables.

=================================================== No Audit Needed it is just a copy of of Dr Bensen's ===============================

To further explain curve graphs here is how Dr Bensen described them.

14. APPENDIX I

TO GYROCOPTER FLYING INSTRUCTIONS

The more technically-minded builders and pilots of Gyrocopters will appreciate the significance of this Appendix and its attached curves.

Two curves have been plotted on the following page, which describe better than words the relationship between flight speed and the engine horsepower of a typical Gyrocopter.

The first plot shows two curves, the solid one being power required to maintain steadystate level flight at a fixed gross weight, and the dashed curve shows engine horsepower available at any given forward airspeed. Several points are worth studying here. Observe first that even when turning at full throttle, engine power is zero at zero airspeed insofar as forward propulsion is concerned. This horsepower rises rapidly to the point where at 15 mph it can maintain level

flight. Beyond this point the pilot must reduce the throttle to maintain level flight. If he chooses not to do so, the craft will either rapidly accelerate to higher airspeeds, or will climb, or both, depending on what he does with his longitudinal stick control. Maximum excess horsepower occurs at 40-45 mph. Finally, at approximate!y 85 mph the “power required” curve crosses again the “power available” curve, which means that the gyrocopter here reaches its “top speed” in

level flight. Higher speeds beyond this point therefore can be obtained only at the expense of losing altitude, or diving.

The second plot illustrates this situation further by comparing it with an airplane of approximately equivalent horsepower and performance. It can be seen that the Gyrocopter performs best in the very area where an airplane quits flying because of stall, at about 40 mph. Furthermore, the Gyrocopter never really “quits flying” even below its “minimum level” speed of 15 mph, but continues to fly at a finite rate of descent. Even at zero forward speed this rate of descent is

comparable to that of a parachute.

One lesson a new Gyro pilot must learn after studying these curves is this: whenever he finds himself slowing down accidentally or on purpose to 15 mph (or if banked in a turn, to 20-25 mph), the only way he can check his descent, or initiate a climb, is to dive momentarily to 40-45 mph while opening the throttle wide open. If in a turn, also flatten out the bank as soon as possible. This may seem like an odd thing to do, especially if you are already close to the ground, nevertheless, if you want Mother Nature to cooperate, that is the proper thing to do. Your effort in will power will be richly rewarded by the gyrocopter possessing at 45 mph the rate of climb of

“a homesick angel”, pulling you out of tightest spots as it heads for the sky.

Also obvious from these curves is the “negative drag slope” below 45 mph, which means that, at a given power setting, the machine will constantly try to either speed up or slow down. To maintain constant airspeed below 45 mph then the pilot must constantly manipulate the throttle up and down to imitate governor action.

Other clarifications of the relationship between the horsepower and the airspeed will become apparent to you at length, if you take time to memorize and study the attached curves. Please note that the curves were drawn purposely not to scale to allow for the variation of performance between individual gyrocopters.

Here is an example of an accident: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AheudQuxZZY

Attachments

Last edited: